A Shot at Space: Validating Rocket Integrity With Thermal Imaging

Neil Tewksbury and his team at the University of Southern California Rocket Propulsion Lab want to blast a rocket into space. As part of an unofficial space race among international universities, Tewksbury and his team don’t just want to be the first team to successfully launch; they want to reach an altitude of 100 km (330,000 ft) above sea level with a rocket made up completely of components that they manufacture themselves. They only get to build one or two rockets every year, so testing components on the ground is essential to building viable rockets.

The Challenge

As part of his application to obtain a launch window from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Tewksbury needed to validate that his space-shot rocket could safely make the trip. Part of that validation process took place at a Mojave Desert test site. Tewksbury needed to test the integrity of the thermal protection system of the rocket’s motor case as well as the carbon-phenolic nozzle design. “We have to guard the case, which actually can’t survive very high temperatures because it’s carbon fiber,” Tewksbury said.

“The biggest new addition to this static fire was the nozzle. We completely redesigned the nozzle with new materials, new processes,” Tewksbury added. “We wanted to see how well that performed. We used a special ablative* technology on the nozzle to hopefully whisk away as much of the heat as possible to protect our thermally sensitive case.” Called Graveller II for “ground” and “traveler,” this was to be a static test of the rocket motor on the ground.

In past static tests, Tewksbury relied on thermocouples to gather thermal management data. Whereas thermocouples could provide specific spot data, he needed a solution that could gather more comprehensive data for this test. “We really wanted to see if there were any hot spots both on the case and on the nozzle. We can only use a finite number of thermocouples,” Tewksbury said.

*Ablative material is designed to slowly burn away in a controlled manner, so that heat can be carried away from the spacecraft by the gases generated by the ablative process while the remaining solid material insulates the craft from superheated gases.

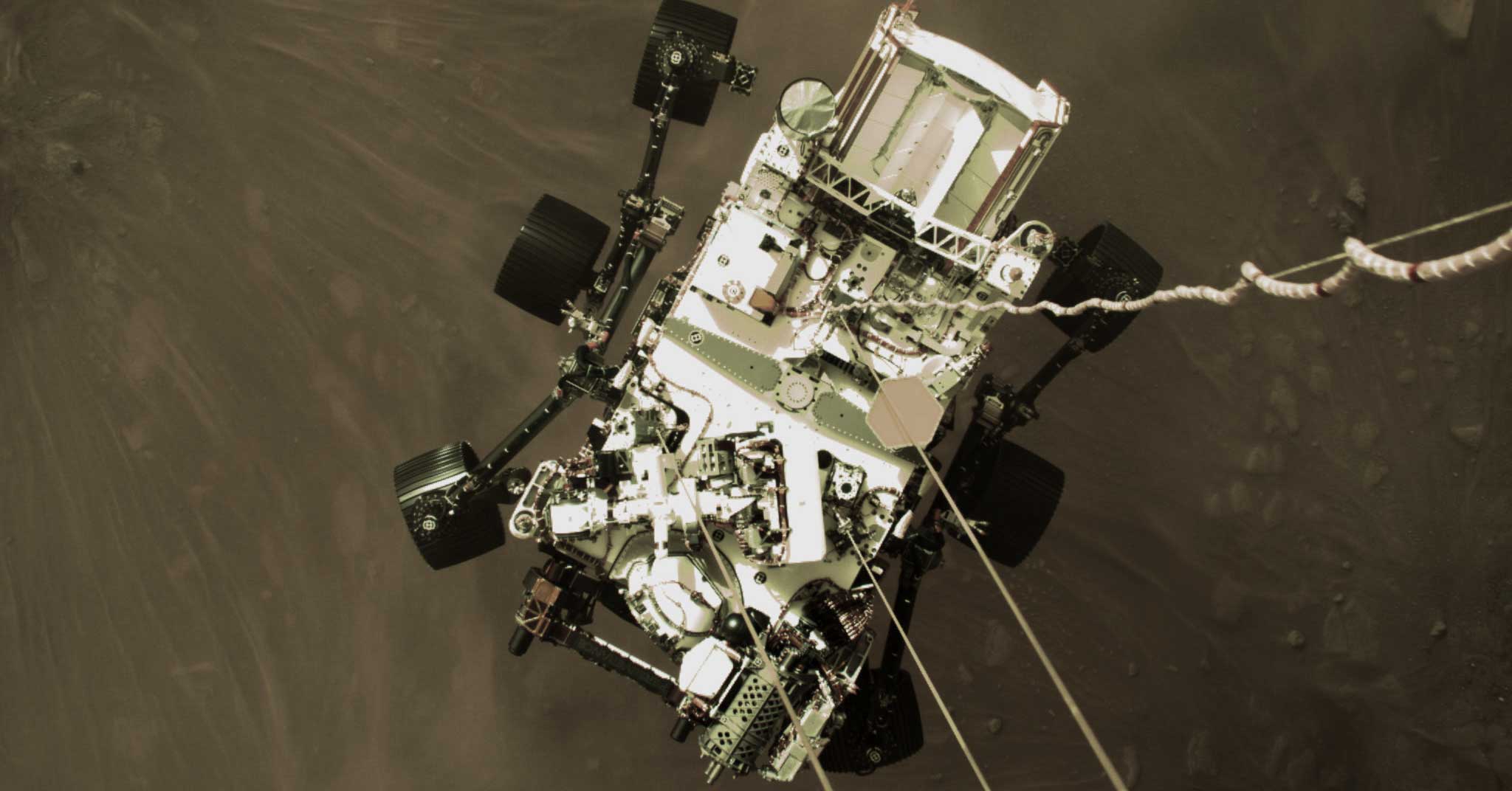

Rocket testing sequence as seen by the FLIR T540.

The Solution

On February 17, 2018, the USC Rocket Propulsion Lab successfully tested Graveler II, the largest composite-cased amateur rocket motor ever successfully fired to date. The 8-inch diameter, 80.5-inch long R-class solid rocket motor delivered a total impulse of 42,000 lbf-sec. Graveler II was fired in a carbon-epoxy motorcase with a carbon-phenolic nozzle, all of which were designed and fabricated by USC students. Prior to testing, Tewksbury reached out to a FLIR representative who visited his classroom to discuss infrared technology and asked if he could possibly borrow a camera. FLIR was able to provide a T540 professional handheld camera for the testing, which Tewkesbury found very intuitive and easy to use. He only needed to watch a brief tutorial video on the FLIR ResearchIR software and he was ready for the test firing.

Tewksbury painted the rocket matte black to ensure constant emissivity and reduce reflection as much as possible. On test day, he powered up the T540, plugged the ambient conditions of the Mojave Desert test area into the camera, and placed it far enough away to keep the camera safe while maintaining a tight field of view.

One of the main reasons Tewksbury wanted to use a thermal camera was to conduct a failure investigation if their design failed. But the test was a complete success so no failure investigation was necessary. “The rocket worked perfectly. I also got some meaningful data about how the thermal protection system manages the heat.” Following the rocket firing, Tewksbury continued to gather thermal data on the cooling rocket. “Well after the burn, a couple of minutes, you can actually see the boundaries between our grains. Our motor is actually five or six chunks of propellant stacked on top of each other—it’s called BATES grains—you can actually see the gaps between the grains as hot spots. So we knew that we could quantify how the heat was being transferred.”

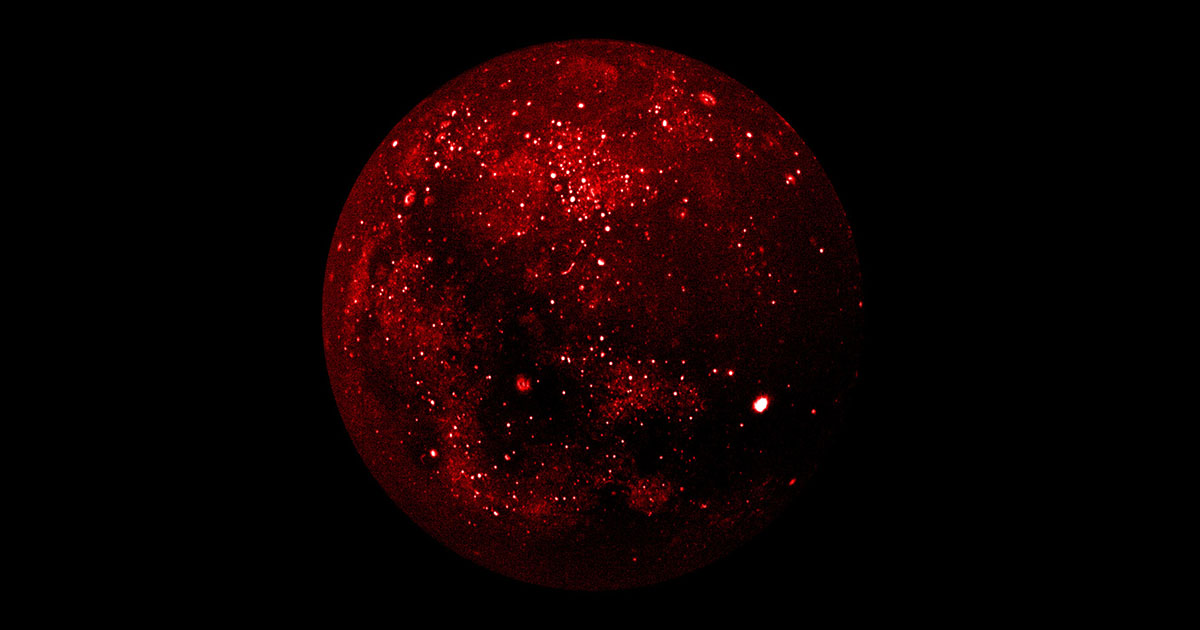

BATES grains still evident after the rocket test.

With these results, Tewksbury and his team are close to obtaining their launch window from the FAA and hope to reach the Karman Line (100 km above sea level) somewhere above Black Rock, Nevada. They’ll team up with an avionics team from USC that will be responsible for flight software, sensors and parachute deployment. “We’re going to reach just beyond the Karman Line and then fall back—under a parachute, of course."